The human eye transcends the merely medical, functioning as a symbol for so much more than a pair of tiny organs. “The eye is the window to the soul;” we see “eye to eye” when we agree; “an eye for an eye” means revenge; someone we love is the “apple of our eye.” Medical care focused on eyes is known to extend back to at least the 1750s BCE, as a doctor treating the eye with a bronze lancet is mentioned in the Code of Hammurabi. From lancets to lasers, magnifying glasses to contact lenses, the history of eye care forms an important and unique part of our medical history. The Medical Artifact Collection, made up of a mix of artifacts from London and the surrounding area between the late 1700s and today, is home to a wide range of eye-related instruments, treatments, and other objects, showing the importance and centrality of eye care to the history of human health. These two cases feature artifacts relating to eye health in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Southwestern Ontario. Can you guess what these artifacts are? Click the button below the image to see the artifact record and learn more about it! “Much has been written, ranging from the valuable to the worthless, about the invention of eyeglasses; but when it is all summed up, the fact remains that the world has found lenses on its nose without knowing whom to thank.” Vasco Ronchi, Italian Physicist

More Than Meets the Eye: The History of Eye and Vision Care

Featured Artifacts

What Am I?

What Am I?

What Am I?

What Am I?

What Am I?

What Am I?

What Am I?

What Am I?

Vision Testing

Invented in the 1890s, this lantern was originally used to test for colour blindness in railway workers. The dial of coloured disks on the front would rotate to shine coloured light at patients, who would have to identify the colours as fast as they could. This was important for railway workers because their jobs required them to be able to recognize different coloured railway signal lights to prevent accidents.

Dr. C.H. Williams' Lantern for Testing Color-Sense

The Ishihara test, which uses plates of coloured dots arranged in a recognizable pattern or symbol that may be invisible to someone with colour-blindness, was introduced by Japanese ophthalmologist Shinobu Ishihara in 1917.

Ishihara Test

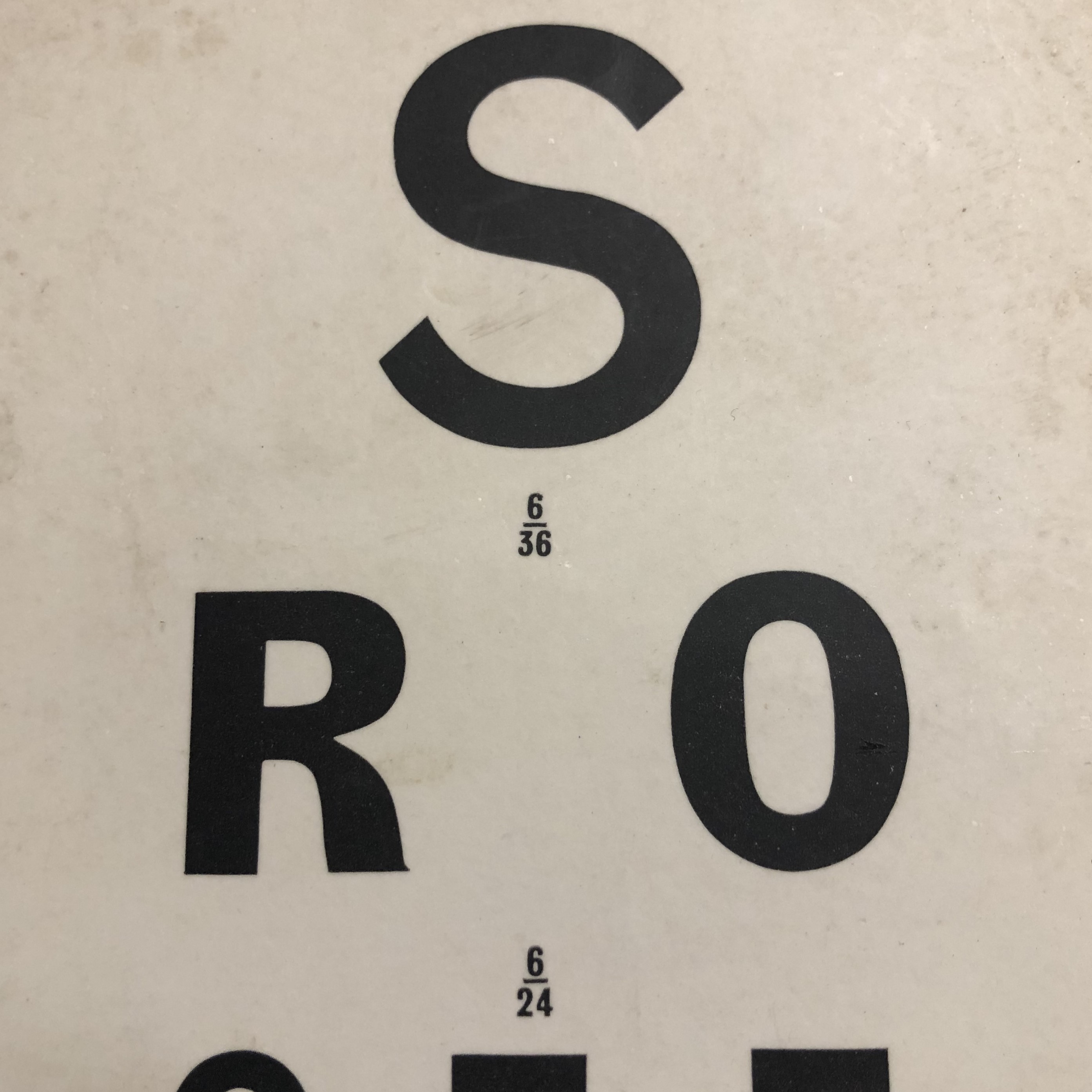

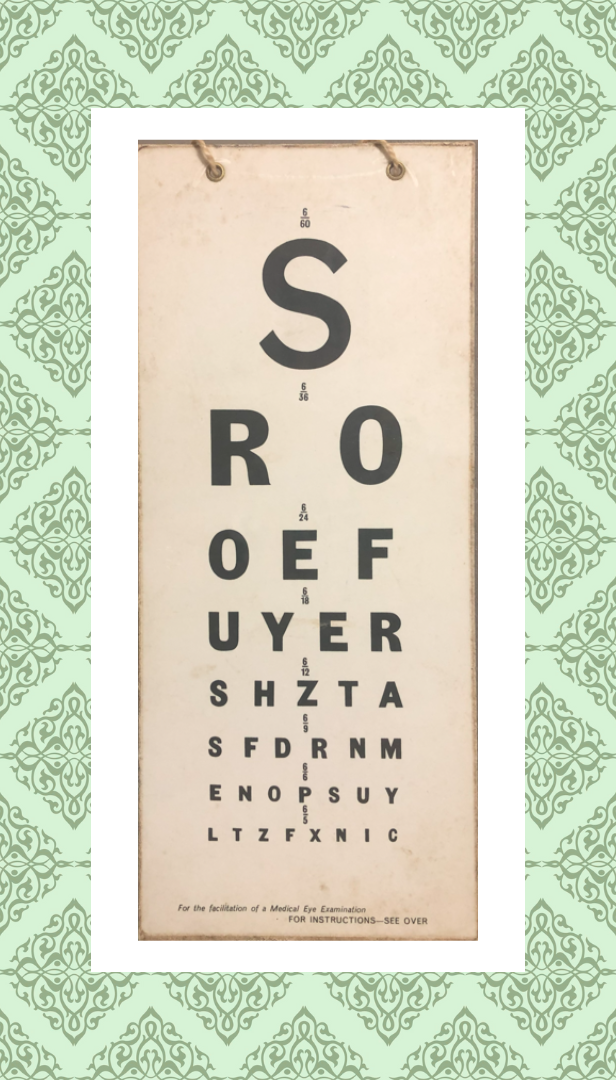

The Snellen eye chart, invented by Dutch ophthalmologist Herman Snellen in 1862, is still commonly used today. The rows of letters test clarity of vision at different distances, measured against the standard for normal human vision. This chart uses metres rather than feet (6/6 refers to what may normally be seen from metres away, equivalent to 20/20 vision), and has been scaled down for use at a distance of three metres.

Snellen Eye Chart

Eyeglasses

Made for people whose eyes were sensitive to light, these early-to-mid twentieth century rose-tinted test lenses were advertised to cut down on glare and protect the eyes. The test lenses in our collection are tint gradations 1 and 2, so the rose-colour is barely noticeable.

Soft-Lite Test Lenses

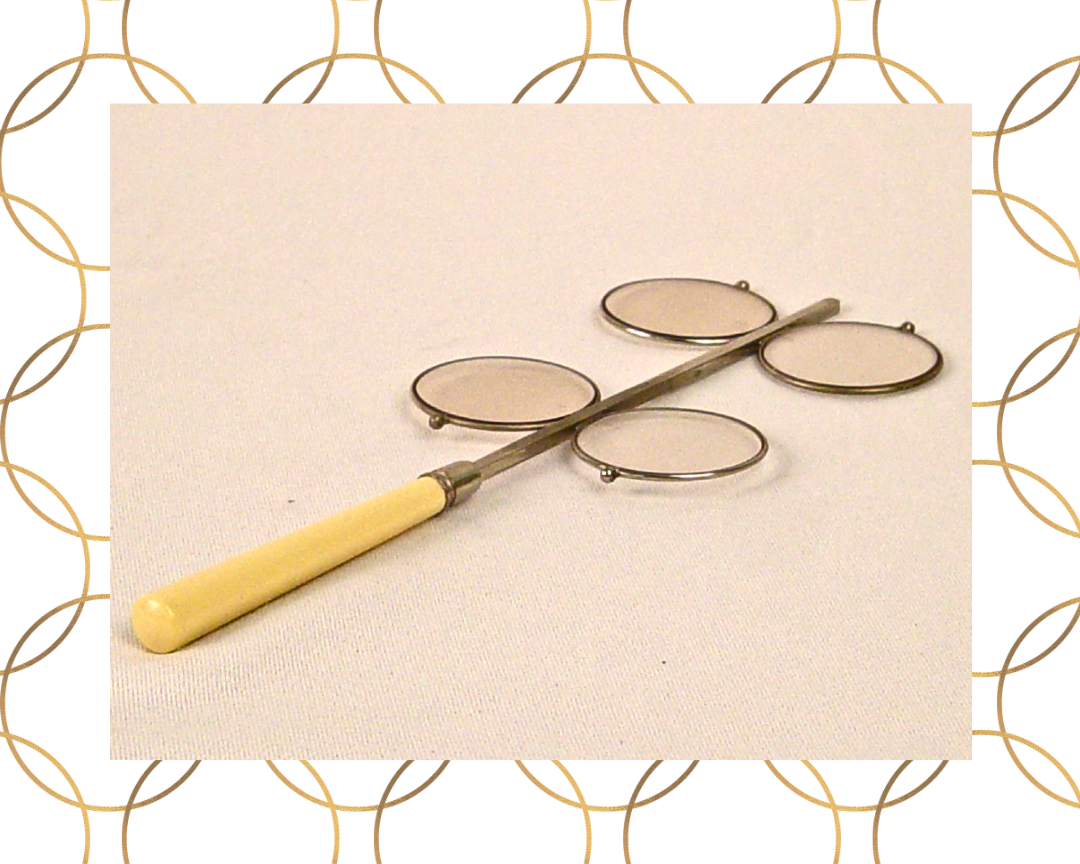

Pince-nez are a style of eyeglasses that do not have temple pieces that sit over the ears, instead being held in place by tension across the bridge of the nose. They were especially popular in the late nineteenth century, and were often attached to a chain because they could fall off and be lost easily.

Pince-Nez Glasses

Bifocals were invented in the late 1700s by Benjamin Franklin, American statesman. He had grown tired of having to switch what spectacles he was wearing to focus on different distances, and solved the problem by cutting the lenses of his glasses in half horizontally with one half for long distances and the other for things close up. He wrote in 1785 “By this means, as I wear my spectacles constantly, I have only to move my eyes up or down, as I want to see distinctly far or near, the proper glasses being always ready.”

Bifocals

Eye Surgery

Equipment

Pharmacy

Eye Baths have been used since the 1500s for cleaning and administering medication to the eyes. They have been made of many different materials over the centuries, including glass, silver, and aluminum.

Eye Bath

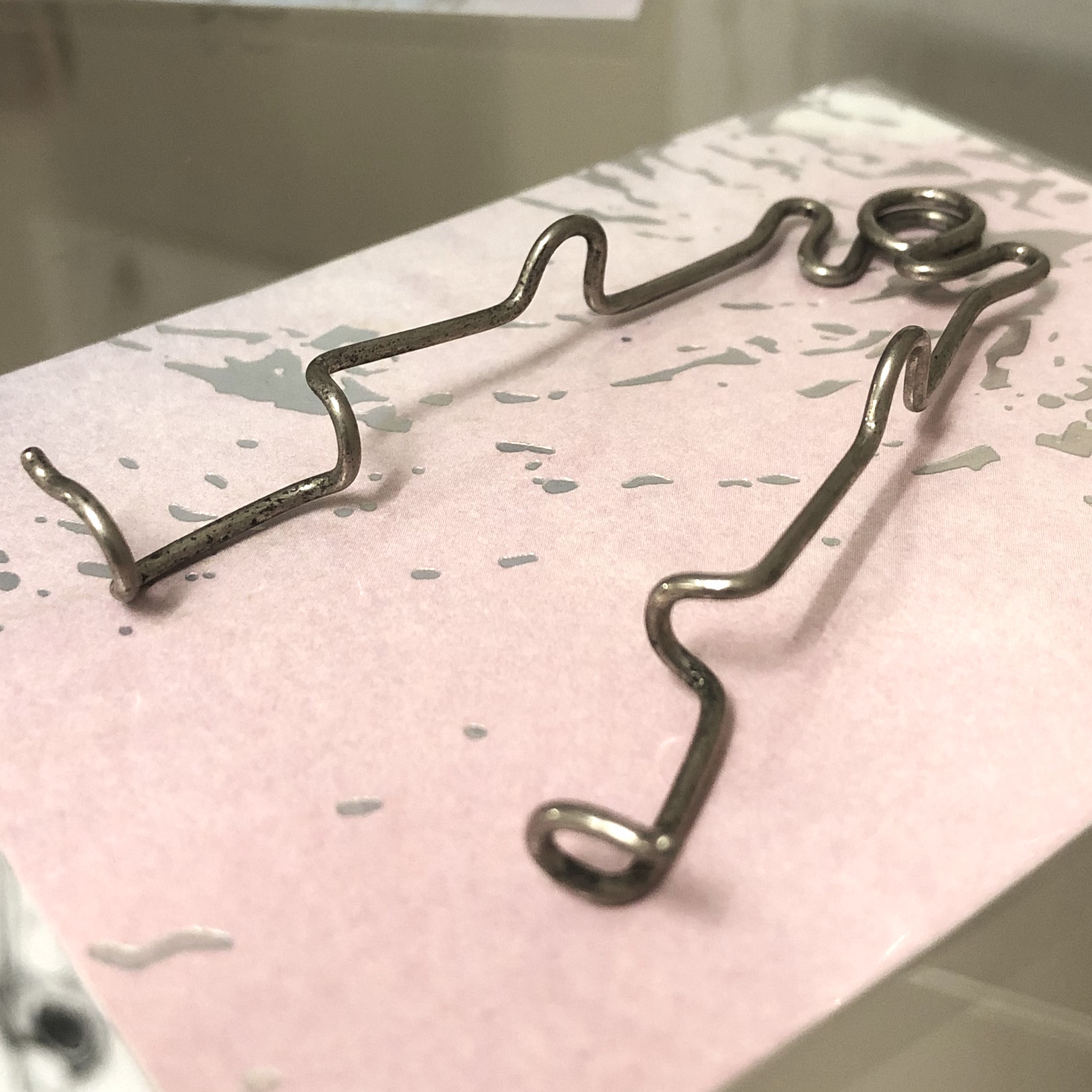

In the late 1800s, silver nitrate was used on newborns’ eyes to prevent neonatal ophthalmia, a type of conjunctivitis, or pink eye, often caused by bacterial infection during the birthing process.

Silver Nitrate Applicators

Belladonna, from the Italian for “beautiful lady” because of its historical use by women to dilate their pupils for aesthetic purposes, has been used on the eyes for centuries. In the mid-nineteenth century, belladonna was used to treat blindness caused by cataracts, foregoing the need for surgery because the pupil becomes so dilated that the cataract is no longer obstructive. It was noted especially for the observation that its effects did not decrease with much use, as did those of many other medications. It is still used to dilate pupils today in the form of atropine eye drops.

Belladonna

Exhibit Under Construction! Check Back Soon for More Content!

You are using a browser that is not standards-compliant. The information on this Web site will be accessible to you, but for a list of Web browsers that comply with the World Wide Web Consortium standards, please visit our Web standards page.

May 2024

Lawson Hall, 2nd Floor

Ancient Egyptians and Persians used people’s ability to see specific stars as a way of testing visual acuity. These stars could be considered early “optotypes,” agreed upon symbols or visuals that serve as a standardized measure of visual acuity. Later centuries, from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth, saw the development of other methods, including mustard seeds, lines and grids, figures, and finally printed type (words and letters). The viewing angle and distance are very important when formulating a good eye chart, as well as consistency in the changes in size between one line and the next. A good chart should use symbols identifiable by anyone, and the struggle for a globally standardized eye chart persists today.

No one really knows who first invented eyeglasses, and this question has been the subject of debate for centuries. The best answer we have is that they were invented in present-day Italy around 1286. These glasses could only improve near vision, and evolved from “reading stones,” which were shaped pieces of glass used to magnify text. The pince-nez style of glasses came into use in the 14th century, and by the early 1700s, “temples,” or arms, were added to the design. Later innovations like new materials and styles for frames, the invention of bifocals, progressives, and contact lenses give us the wide range of eyewear we see today.

hh

hh